Este artículo también está disponible en: Español

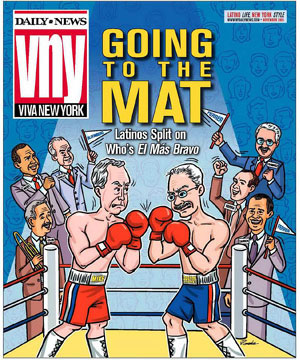

November 2005For the first time ever –and after quite a few attempts– a Latino New Yorker is a mayoral candidate in a general election. Only months after Antonio Villaraigosa’s historic victory in Los Angeles, you would expect every single Latino volunteer, activist, community leader, elected official and political advisor in New York to be sweating 24/7 to get Fernando Ferrer elected.

Right?

Not so fast, compadre.

Although it faces the best-known Latino politician in the city, Michael Bloomberg’s reelection campaign is not giving up, trying to snatch as many Latino voters as possible from under Ferrer’s feet.

The main weapon in the Republican mayor’s strategy is a group of highly-visible Latino politicians, both Democrats and Republicans, with decades of experience in local politics, who make up the mayor’s “Hispanic outreach” team and are not a tad shy about attacking Freddy.

“He thinks that, for the simple reason that his last name is Ferrer, every Hispanic ought to vote for him. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way,” says Fernando Mateo, a loquacious Dominican businessman, activist and registered Republican who serves as the team’s director and Ferrer critic-in-chief.

Like Mayor Mike in City Hall, the Bloomberg Latinos work out of a bullpen at the spacious campaign headquarters, on a 19th floor office overlooking Bryant Park. The team includes former Board of Education President Ninfa Segarra, a one-time Ferrer ally, former Pataki aide Shirley Rodríguez-Remenesky, and Dominican-born journalist Maxy Sosa, who deals with Latino media. Salsa great Willie Colón and Latino political pioneer and former Congressman Herman Badillo serve as two of the campaign’s chairmen.

Naturally, their choice of the Republican white billionaire over the Democratic Nuyorican in the fight of his political life does not sit well with Ferrer’s supporters and allies, some of whom even call them “mercenaries”.

The Bloomberg Latinos complain that Ferrer did not remain visible after his 2001 runoff loss to Mark Green and the 9/11 attacks, and argue that Bloomberg has been just too good of a mayor to let ethnic pride get in the way.

“This time I can’t vote for a Latino just because he’s a Latino,” says Rodríguez-Remenesky. “I have to vote my conscience.”

Emphasizing the fact that Latino elected officials all over town are behind Ferrer, his supporters dismiss the Bloomberg team as a bunch of hired hands with no real influence on voters.

“They think that, because they can hire a lot of people, this means having Latino support,” says Luis Miranda, the former president of the Hispanic Federation and one of Ferrer’s closest advisors along with his business partner, former Bronx Democratic Party boss Roberto Ramírez.

“(Bloomberg) has employed many Latinos, but right now he doesn’t have the support of any Latino elected official.”

“They are a very tiny minority,” says Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión. “(Bloomberg) can pay people quite a bit of money, but for me that is not an indication of the sentiment in the Hispanic community.”

According to the Ferrer campaign, their candidate does not need advisors to be able to reach Hispanics. “Because he is a real New Yorker, he is connected to the community,” says spokeswoman Maibe Gonzalez. “He does not need to repair that disconnection the mayor has.”

“We have to wonder, do these politicians (supporting Bloomberg) really have any influence in our communities,” says Upper Manhattan councilman and Ferrer ally Miguel Martínez. “They are defending their jobs rather than political or social ideas… They are mercenaries, they do it for a salary.”

In trying to explain the lack of endorsements from Hispanic elected officials, those in the Bloomberg camp claim Bronx Democratic leaders are ready to punish anyone who dares stray from the party lockstep. “They scare people,” Mateo says. “They say, ‘I’m going to put up a candidate against you.’ That’s not how you work.”

In trying to explain the lack of endorsements from Hispanic elected officials, those in the Bloomberg camp claim Bronx Democratic leaders are ready to punish anyone who dares stray from the party lockstep. “They scare people,” Mateo says. “They say, ‘I’m going to put up a candidate against you.’ That’s not how you work.”

Analysts say the split among Latino politicians, at the historic moment when a Latino finally has won a major party nomination, points to deeper conflicts in the increasingly diverse Latino political landscape in New York.

One such conflict is the tension between the Bronx Democratic leadership – the traditional nucleus of Puerto Rican power in the city – and those outside of that group.

“Freddy basically didn’t reach out to enough people,” says Ángelo Falcon, president of the Institute for Puerto Rican Policy. “People would have liked to be approached by him, but he is not very welcoming to people. Then it’s easier for them to go with Bloomberg, because Bloomberg was reaching out to them.”

On the other hand, Falcón adds, politicians not affiliated with the Bronx power structure are made “uncomfortable” by the possibility of a Ferrer mayoralty. “If the Puerto Rican mafia is in charge of City Hall,” he says, “people feel they are going to get a better deal from Bloomberg.”

Ferrer begs to differ. “My campaign represents the New York rainbow, especially in our community. My two top advisors are Latinos”, he said in the middle of a recent morning of hard campaigning. “There are also many Hispanic volunteers and donors who approach our campaign in good faith.”

Despite the money being poured into the campaign and the effort by the mayor’s Hispanic team, a significant majority of Latinos is still expected to go Ferrer’s way. A July Hispanic Federation poll found Ferrer would beat the mayor two to one –54% to 27%– among Latino voters. And in September, the first Quinnipiac University poll after the primaries had 57% of Hispanics choosing Freddy and 31% leaning Bloomberg’s way.

One neighborhood that is hotly contested is predominantly Dominican Washington Heights, where the Bloomberg campaign opened an office in August. Although experts say Dominicans are likely to vote in similar patterns as Puerto Ricans, the mayor’s people are clearly betting against this and hoping for a particularly good performance in Upper Manhattan.

Ana Viña, a resident of 181st St., is their dream voter. “I don’t want to hear about the Hispanic guy, because I never liked him,” she said at the Laundromat on her block on a recent sunny morning. “I like Bloomberg. He’s done a perfect job… He’s not going to be looking for money–he’s going to work for the people.”

A few blocks away, Águeda Solano, 61, said she’s voting Ferrer. “I don’t like Bloomberg because he’s too much of a businessman,” she said, adding that the mayor cares about corporations rather than people: “Ferrer cares about the community and I like that a lot.”

Ferrer depends both on a commanding lead among Hispanics and a big turnout by them. Last month, he scored a major victory when he received the endorsement of the city’s powerful SEIU Local 1199 health-care workers union, led by Puerto Rican Dennis Rivera. The 117,000-strong union has an impressive get-out-the-vote operation that can make a difference on Election Day.

Another major factor to be measured is the black vote, where Bloomberg seems to have made substantial inroads and which Ferrer needs to win to have a shot at living in Gracie Mansion. The same Quinnipiac poll had 46% of black voters favoring Ferrer and 39 % for Bloomberg.

It is unclear whether the presence of the Bloomberg Latino team –and the mayor’s favorable poll numbers among Hispanic voters– also signal a Latino migration across party lines.

“There is a drift towards the G.O.P. across the country by some elements of the Latino community. This points to the diversity of the Latino community,” says professor Philip Kasinitz, chairman of the sociology department at the CUNY Graduate Center.

In New York, he adds, this diversity is expressed in groups like South American middle-class homeowners from Queens, who are unlikely to vote like Bronx Puerto Ricans and among whom Bloomberg did particularly well in 2001.

Other analysts, including Falcón, say that while large numbers of Latinos in New York may vote for top-of-the-ballot Republican candidates such as Bloomberg, his predecessor Rudy Giuliani and Governor George Pataki, they remain loyal Democrats at heart.

But even a Democrat such as Dominican-American Queens Assemblyman José Peralta acknowledges young pols like him have a hard time finding room to grow inside the established structure of their own party–which may push some towards the G.O.P.

Democratic leaders, he says, “have to be a little more inclusive. Some are not paying attention to the new generation. Republicans are doing a good job in communicating their position to new immigrants: ‘We are here, with our arms open.’”

Whether the Bloomberg Latino offensive will pay off remains to be seen. Until the eve of Election Day on Nov. 8, the two camps, whose players have known one another for many years, will be lobbing plenty of rhetorical hand grenades from one trench to the other.

Ferrer “doesn’t have the kind of vision and leadership qualities that you need” to be mayor, says Ninfa Segarra, who went to high school with him. “Some day, there will be a Latino candidate who’ll do that, but Freddy is not that candidate.”

The Bloomberg Latinos, answers Carrión, still have time to change their minds.

“Although they are being paid by the campaign, I hope that, in their private moment at the polls, they will do the right thing for the political development of our community,” he says. “Everyone has to live with their conscience.”

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)  Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)

Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)  Leaving Wall Street (2006)

Leaving Wall Street (2006)  Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)

Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)