The revolutionaries are among us. They walk the streets of Washington Heights and the Bronx; they root for the Yankees and for Pedro; they own a bodega, or sell insurance, or hold the elevator door open for you.

When spring comes, they remember April ’65. That was when la Revolución de Abril immersed the Dominican Republic in a civil war. The Johnson administration reacted by sending more than 22,000 troops to prevent a victory by rebels it perceived as dangerously leftist.

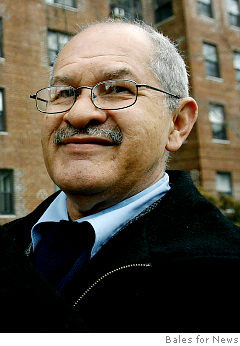

“Our fight was for democracy in the country,” said Cristian Estévez Gil, 64, a former Dominican Army sergeant major, who today is a building superintendent in a quiet corner of Riverdale in The Bronx.

- Cristian Estévez Gil.

“That the country would be democratic and that everyone would have a job, that was what we wanted.”

On April 24, 1965, pro-democracy Dominican officers rebelled against a right-wing government which 19 months before had deposed Juan Bosch, the country’s first freely elected president.

The rebels – and thousands of civilians who joined the fight – are remembered as the constitucionalistas, for they demanded that the 1963 constitution be respected.

“We wanted to reinstate President Bosch’s government, which had been usurped by a group of military officers and the national oligarchy,” says Andrés Hernández, 65, who was a second-year cadet when the revolution started.

Today he’s a lab supervisor in a designer clothing factory in New Jersey and lives two floors above his friend Estévez.

The constitution of 1963 had been written after the assassination of longtime dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo led to an unprecedented democratic opening. Bosch, a left-of-center politician, attempted moderate social reforms during his seven-month term.

Four days after the revolution started, the American ambassador forwarded Washington an urgent request by the governing junta to send “unlimited and immediate military assistance” to stop a rebellion that had an “authentic Communist stamp” and would “convert this country into another Cuba.”

Hours later, with the stated purpose of protecting American citizens in the Dominican Republic, the first direct U.S. military intervention in Latin America in more than three decades had started.

“We had cornered [the military junta forces] and we were winning,” says former Capt. Miguel Zapata, the New York president of the Fundación 24 de Abril of former constitucionalistas. “Only San Isidro [military base] was left and we were advancing on it when the invading forces arrived. They repressed us, and we had to pull back.”

- Andrés Hernández

A months-long standoff ensued, which ended with the naming of a provisional government and a suspect 1966 election in which Bosch was defeated by Joaquín Balaguer, who would go on to dominate Dominican politics for 30 years.

With Balaguer in power, a ferocious repression was unleashed. Zapata, whose elite team of military divers had a big role in the fighting, says several ofhis colleagues were killed.

“They would run them over with a car or gun them down at night,” he says. The violence forced many to leave their beloved Quisqueya. Some became an early seed of what today is the largest immigrant community in New York.

“They have become integrated into the community and [the revolution] is a separate chapter in their lives,” says sociologist Ramona Hernández, director of the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute.

Still, many former revolutionaries became involved in community issues here, Hernández says. And they spawned a generation of engaged youngsters who looked up to them.

“We wanted to be like Caamaño,” says community activist Radhamés Pérez, referring to revolutionary leader Col. Francisco Caamaño Deñó.

Pérez, 52, vividly remembers seeing a constitucionalista column enter his town of San Francisco de Macorís.

Although the American government said it was preventing a Communist takeover, the rebels were ideologically diverse.

“They labeled us supporters of Fidel Castro and leftist groups, but those were false accusations,” says Estévez.

Zapata, on the other hand, still defends socialist ideals. But he says he hasto live with the irony of having become a U.S. citizen and raised his four children “in the claws of the enemy monster.”

Hernández, an American citizen too, sees no contradiction in that. “I’ve adapted to the American system,” he says.

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)  Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)

Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)  Leaving Wall Street (2006)

Leaving Wall Street (2006)  Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)

Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)