Este artículo también está disponible en: Español

In addition to attending journalism school at Columbia University, in 2006-2007 I obtained a second Master’s degree in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University.

My master’s thesis was an investigation into the dozens –possibly hundreds– of Dominicans who fought against U.S. troops in Santo Domingo during the Constitutionalist revolt of 1965 and later ended up living in New York, some as regular immigrants, others as “guests” of an American government intent on helping right-wing leader Joaquín Balaguer by keeping troublemakers away from the D.R.

What follows is the introduction to the thesis. To download the complete 78-page pdf document, click here.

* * *

The Lasting Echoes of an American Intervention

On April 24 1965 a military revolt erupted in a base outside Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. It was the result of a conspiracy by young officers and center-left politicians to restore legally-elected President Juan Bosch, who in September 1963 had been ousted by a right-wing coup d’état after seven months in power. The rebellion could have been yet another event of military meddling in the country’s politics, a common occurrence since the republic had been thrown in turmoil by the assassination of longtime dictator Rafael Trujillo in May 1961. But in a matter of hours the golpe became a popular revolution when thousands of civilians who wanted to see Bosch return to the National Palace swarmed the streets in support of the officers. Right-wing military leaders reacted by strafing the palace and the neighborhoods close to the Duarte bridge, the main point of access to the city from their base. A civil war had started.

The war lasted four days, which was the time it took President Lyndon B. Johnson to decide he could not countenance the possibility that the revolt might turn the Dominican Republic into “a second Cuba.” Starting April 28, over twenty thousand U.S. troops would land in Santo Domingo and help stop and vanquish the rebels. Although there were a few all-out battles and numerous skirmishes, the defeat would come through extended negotiations while the Constitutionalists –as the pro-Bosch side became known– were cordoned off inside the Ciudad Nueva section of downtown. The following year, American-favorite Joaquín Balaguer won questionable elections and became a dictator in thin disguise for twelve years – during which he was supported and abetted by the U.S.

What Dominicans know as the Guerra de Abril, guerra patria, or Revolución de Abril was one in a string of occurrences of U.S. intervention in Latin America during the Cold War, which sometimes was exerted through diplomatic pressure, and in other occasions through the landing of American troops. Guatemala 1954, the Bay of Pigs 1961, Brazil 1965, Chile 1973, Central America in the 1980s, have become shorthand for historical events determined by one overall logic: U.S. hegemony over the Western Hemisphere in the midst of the East-West confrontation and its proscription of any sign of dissent by the region’s governments.

These events have been duly narrated from various points of view. But Cold War History has been mostly concerned with policymaking, international relations, and similar subjects. We know a lot about what presidents, ambassadors, generals, and intelligence officers did, thought, and wrote during each crisis. Narrations of the individual histories of the “minor,” anonymous, street-level protagonists are harder to find – although some exist too. [1] What we very rarely find out, though, is whatever became of those faceless people, how their lives were affected in the long term by the larger Cold War history in which they were just one more fighter, one more protester, one more detainee.

This study aims to tell the stories of one particular group among the Dominican revolutionaries who in 1965 fought American Marines and paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division in the streets of Santo Domingo. In an ironic but not entirely coincidental twist of Cold War history, a great many of those rebels ended up migrating to New York – some immediately after or even during the revolution, others many years later. The city which any self-respecting Latin American anti-imperialist considered “the belly of the beast” became home to many Constitutionalists. On May 2, 1965 President Johnson explained his decision to intervene to the American public saying that the Dominican “popular democratic revolution” had been “taken over and really seized and placed into the hands of a band of Communist conspirators.” [2] Today, many of those purported “Red agents” live in New York as part of the city’s largest immigrant group. They are members of the city’s local government bodies, they lead community organizations, they work in American and Dominican political parties. Many became American citizens. Their children and grandchildren were born here. The Constitutionalists have become part of the nation that one day invaded and defeated them.

As I hopefully will show on these pages, this is a story of imperialism’s unintended consequences. Like the proverbial elephant in the china shop, during the Cold War the United States repeatedly threw its weight –and military might– around Latin America. On the receiving end of those unsubtle interventions were thousands, millions of people whose lives were changed forever. That is what happened to the Dominican revolutionaries of 1965, the Constitutionalist New Yorkers whose personal histories I intend to narrate here. To them and because of them, the events of 1965 in downtown Santo Domingo still resonate in 2007 in the neighborhoods of Uptown Manhattan. When the first Marines landed in the Dominican Republic forty-two Aprils ago, they were forever changing the history of New York City.

A Note on Methodology

This study is based on personal interviews I conducted with ten men and women who were participants in the Dominican revolution of April 1965. Four of them were members of the Dominican military; the other six were civilians who joined the uprising. The interviews were conducted in Spanish in New York City between April and October 2007. They were recorded in audio and each of them lasted between one and three hours, with most running about two hours. One was a joint interview where two of the subjects were interviewed at the same time. The rest were individual.

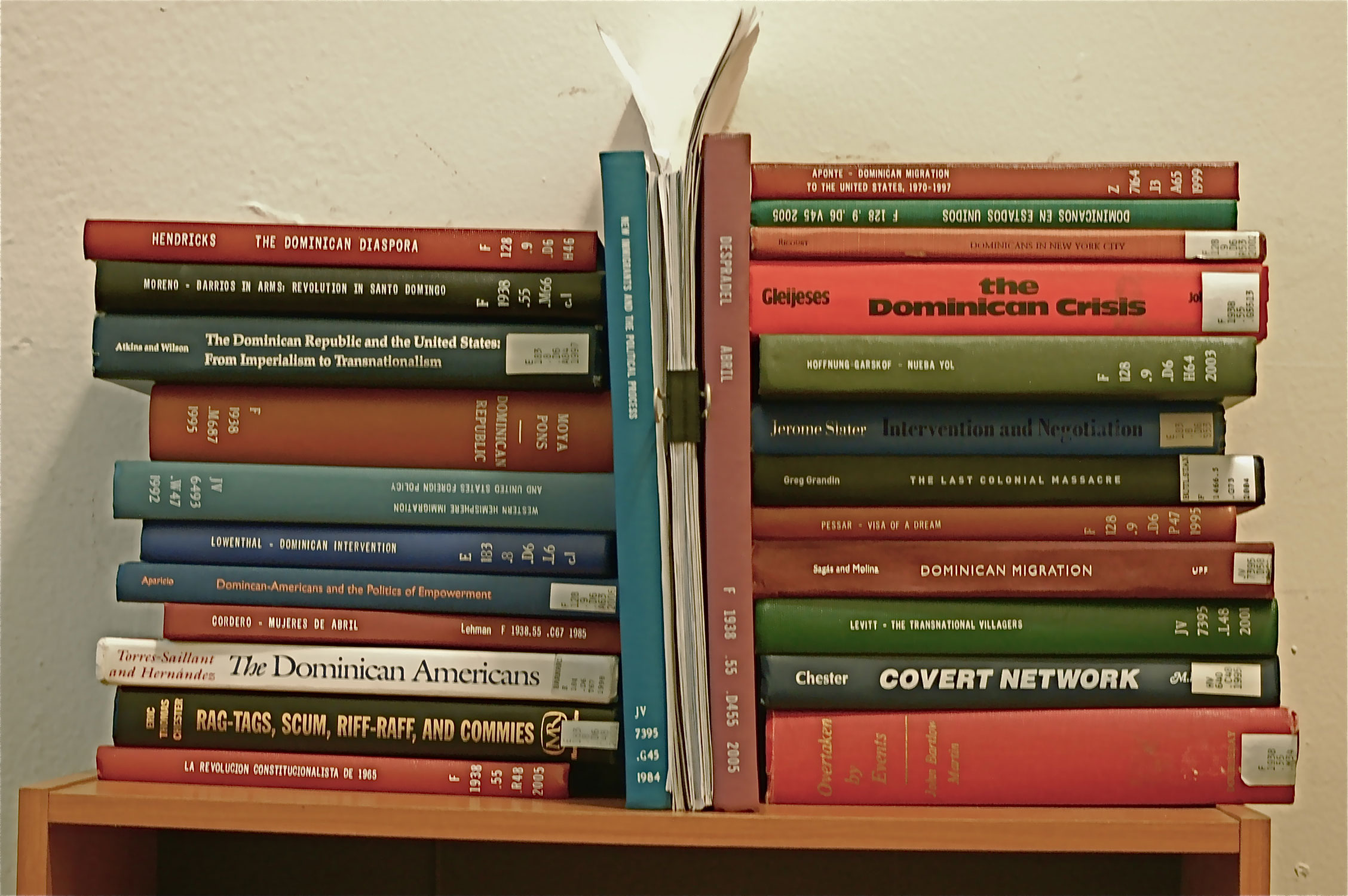

In addition to the interviews, I read a copious amount of material –including books, journal articles, Dominican and American newspapers and magazines– mostly dealing with two main subjects: the Dominican revolution and American intervention of 1965 and subsequent events; and Dominicans in New York, with an emphasis on the community’s social, political and civil organizations.

I have not been able to corroborate all the events described by my interviewees, although I was able to confirm some of them through scholarly and journalistic historical accounts. Because of this, some of their assertions remain unchallenged and would need further corroboration. However, I do not think this detracts from what I set out to achieve in this project.

[1] One excellent example is Greg Grandin’s The Last Colonial Massacre about the Guatemalan Indian peasants who fought on the losing leftist side in that country’s long civil war.

[2] Gleijeses, Piero. The Dominican Crisis: The 1965 Constitutionalist Revolt and American Intervention. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978, 258.

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)  Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)

Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)  Leaving Wall Street (2006)

Leaving Wall Street (2006)  Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)

Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)