A white-and-blue striped flag with a sun bearing a human face is becoming as common on the streets of Elizabeth as the Portuguese red and green, the Italian red, white and green, and the Colombian yellow, blue and red.

The flag belongs to Uruguay, a South American country about the size of Oklahoma.

In the latest immigration wave in a city of immigrants, many Uruguayans have arrived in Elizabeth in the last few years, officials say. Most of those who came entered the United States through a visa waiver program and then stayed illegally.

“It truly was an exodus,” said Victor Medina, vice president of the Newark-based Uruguayan Cultural Group.

“It truly was an exodus,” said Victor Medina, vice president of the Newark-based Uruguayan Cultural Group.

Although no numbers are available of how many Uruguayans have arrived recently, their presence is apparent.

“I’ve noticed them in more restaurants, as waiters. I’ve noticed them working in some of the shops on Morris Avenue, Broad Street and Elizabeth Avenue. I’ve noticed some young people who go to the school system,” Mayor J. Christian Bollwage said. “The growth has been occurring over the last couple of years.”

The arrival was explosive from 2002, when an economic collapse affected the country of 3.3 million, to April, when the United States removed Uruguay from the visa waiver program. This meant Uruguayans were allowed to enter the U.S. for 90 days or less as visitors for business or pleasure without first obtaining a nonimmigrant visa.

Because the influx has occurred since the 2000 Census, Uruguayans are not accurately reflected in the count. But Gerardo Prato, the New York-based Uruguayan District consul for the area, said the influx of Uruguayans has been numerous.

“There always were Uruguayans in New Jersey,” Prato said, “But in recent times, the presence has grown.”

Elizabeth and the Oranges, he added, are “the two big concentrations of Uruguayans.” Prato estimated about 35,000 Uruguayans live in the 11 Northeastern states in the consulate’s jurisdiction.

“Everybody was coming here,” said Silvia, 23, who arrived in Elizabeth with her husband in November, following friends who arrived earlier.

“They told us they were fine, it was different here,” she said, “Their lives had changed, at least economic-wise.”

Silvia does not speak English and refuses to give her last name because she entered the U.S. as a tourist, stayed for more than 90 days and now is here illegally.

“We are in a place that is not ours and they have the right to tell us, ‘Get out,’” Silvia said. “But we did not come here to take anything away from anyone. We came . . . just to help those back home and live here, since there we couldn’t do it.

“If they ever tell us we have to go, we’ll leave and that will be it.”

Silvia is just one of many Uruguayans here illegally. “People who came in the last three or four years,” Prato said, “if they are still here, it’s because the great majority stayed with a visa waiver.”

Uruguay, compared with its neighbors, Brazil and Argentina, is a small country. Known for the warmth and hospitality of its people, it is called “the South American Switzerland” because of its once long-standing democracy and economic stability. Uruguayans affectionately call their home “el paisito” or “the little country.”

The country’s economy, however, is heavily influenced by its two neighbors. When Argentina’s economy crashed in December 2001, it was not long before the crisis crossed into Uruguay. “In March, we had our own financial collapse,” Prato said.

Pushed by unemployment and recession, young people and entire families left the country. Uruguayan passport holders did not need a visa to enter the United States for tourism or general business purposes because of the visa waiver program in effect since 1999.

The high number of entries, Prato said, finally precipitated the exclusion of Uruguay from the program in April. But Stuart Patt, spokesman for the Consular Affairs Bureau of the State Department, said those decisions are “based on a lot of factors, only one of which is the rate of overstay.”

Some of those factors, Patt said, are the general economic condition and unemployment rate of a country, the rate of U.S. visa denials to nationals of the country and the fraudulent use of the country’s passports, sometimes by nationals of third countries.

“Now,” Prato said, “the migratory flow from Uruguay to the U.S. is practically zero.”

Before April, though, Uruguayans arrived daily.

“A friend of mine transported people from the airport (to Orange) and he would bring 14 or 15 every day,” said Medina of the Uruguayan Cultural Group. When rumors spread that the visa program was about to be suspended, the number of arrivals jumped, he said.

“People gave up their homes in exchange for four (airplane) tickets,” he said. Many arrived with nowhere to spend the first night.

“Now you see (Uruguayans) everywhere,” said Medina, 55, a Roselle Park resident who owns a shop in Orange. “It seems you’re living in the paisito because you see people drinking mate , (wearing) soccer jerseys, you hear the way they talk.”

Mate is a very popular drink in Uruguay. Drinkers pour hot water from a thermal bottle into a gourd loaded with an herb called yerba and then sip in turns through a straw. Uruguayan immigrant Ruben Lamaison, 64, the owner of Pizzeria Uruguay in Peterstown, said he is renovating the restaurant because of the new flow of customers.

“Shops are adding products from Uruguay,” the Roselle resident said. “You notice there are people, there is a demand.”

Such is the demand that Carlo Pietrangelo, the owner of Alwilk Music record shop on Broad Street, estimated sales of CDs by Uruguayan artists have increased 70 percent in the past two years.

Pietrangelo set up a whole new section in his store, labeled “Argentina-Uruguay,” to cater to the new wave of customers. “It’s normal to see 20 or 30 Uruguayans coming in every day,” he said.

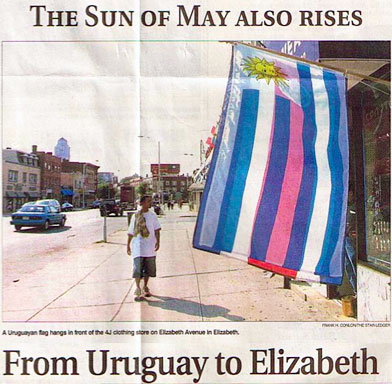

A clothing shop on Elizabeth Avenue known as 4J, sells flags, key chains, baseball caps, T-shirts – everything bearing the national colors of Latin American countries. As a response to the growing demand, employee Jose Garcia said, the store’s owner recently ordered custom-made do-rags with Uruguayan motifs.

“We sell a lot of those,” he added, pointing to women’s tank tops with the sun with a face – known as the Sun of May – and white-and-blue stripes.

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)

Every-Night Fever at the Milonga (2007)  Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)

Migrants Suffer in Mexico (2006)  Leaving Wall Street (2006)

Leaving Wall Street (2006)  Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)

Torn Up Over Being Torn Down (2004)